This article first appeared in National Defense Magazine on 8/8/18.

By James Marceau

Since its introduction to government contracting some 20 years ago, performance-based logistics (PBL) contracting has often delivered the intended result — to improve warfighter readiness through better weapon system availability and reliability, at lower cost.

The intent is to shift responsibility for outcomes to suppliers while also lowering overall lifecycle costs. From the Defense Department perspective performance-based logistics contracts can work, and there is a renewed push to use them. The question then is how is this working out for suppliers since the shift of responsibility also gives them much more of the risk-share?

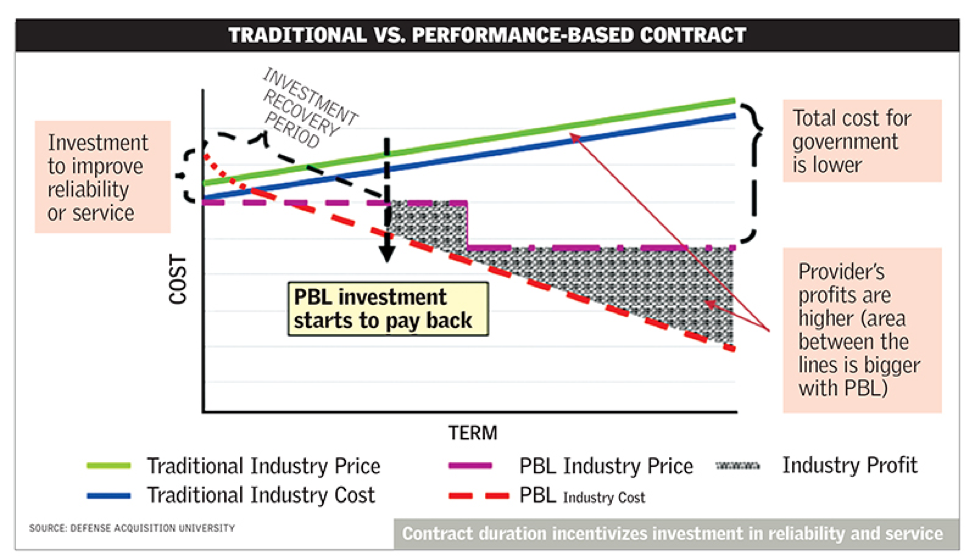

Supplier incentives have been reversed from “the more spares and repairs I can sell, the more profit I can make” to “the less I use, the more profit I can make.” In concept, this is exactly what the department has been trying to achieve more broadly in its relationship with industry — to drive innovation and provide better solutions at lower cost. To help sell the benefit, the graphic from the

Defense Acquisition University demonstrates the potential increase for supplier profit from using performance-based contracts.

The idea is that instead of selling, for example, a weapon system and then selling replacement parts, repairs and maintenance, a supplier signs up to deliver the reliability and availability of a system at certain agreed-to levels. This shifts the supplier/customer relationship to a focus on outcomes versus transactions.

The incentive for suppliers is that it encourages long-term planning and investment in improvement with a business model that can provide higher margins to reward improvements such as: better inventory management, including the opportunity to reduce stock; better resource planning through opportunities to reduce labor costs; and fewer but higher-priced long-term contracts via opportunities to reduce overhead costs. The key word here obviously is opportunity. The supplier’s challenge, and risk, is turning opportunity into tangible, improved financial results.

Why don’t PBL programs always deliver the anticipated margin improvements?

Making the transition from a “spares and repairs” business to a “reliability, availability, maintainability and supportability” enterprise requires a cultural overhaul. The focus changes from discrete stove-piped performance, modification and modernization efforts as directed by customers, to a focus on product and process improvements that are self-generated and that will reduce demand, increase time-on-platform, decrease response time, and mitigate “diminishing manufacturing sources and material shortages” and obsolescence risk. Yet the supplier’s operating model, infrastructure, culture and supply chain all have evolved to support transactional, activity-based, or cost-plus pricing and execution. Given this historical approach, we find most suppliers suffer from several challenges.

One of them is business planning. That includes a lack of a sound contracting strategy, approach and decision-making process: when does it make sense, how to set it up/execute, who to partner with and who owns what, and so on.

Another problem is customer agreements. An example is not partnering with the customer early to ensure a well-constructed product support agreement with clear outcomes, measures and governance — including clear agreement on customer responsibilities and the implications of the customer not meeting their obligations

Some lack a sound business analysis. They fail to employ a robust predictive system with rigorous forecasting and long-term planning tools to understand and mitigate risk, ensure it is priced and managed appropriately, and adequately assess the cost of service requirements and the impact of changes.

Driving sustainable change is another issue. There will be resistance and barriers to investments in improving product reliability, infrastructure, information-technology systems and data management, both internal and customer-facing.

And then there may be a lack of continuous improvement process and culture.

That includes standard and repeatable processes to innovate, drive cost out, compress the supply chain, optimize the repair planning and execution process, and manage the outcomes.

Further complicating matters, despite the success of — and the Pentagon’s push for more — PBL contracted programs, most aerospace and defense contracts are still transactional in nature, so suppliers are primarily incentivized to conduct business as usual. It’s difficult to drive and sustain the necessary organizational changes to make them successful when these programs remain a small portion of the overall business.

So, can individual PBL contracted programs be successful within larger organizations that are set up to transact? The answer is not only yes, but they better be. The following objectives of PBL contracts should be shared by any defense supplier looking to increase its competitiveness in the market: increased material availability; decreased logistics response times; decreased repair turn-around-times; and major reduction of awaiting-parts problems.

So, can individual PBL contracted programs be successful within larger organizations that are set up to transact? The answer is not only yes, but they better be. The following objectives of PBL contracts should be shared by any defense supplier looking to increase its competitiveness in the market: increased material availability; decreased logistics response times; decreased repair turn-around-times; and major reduction of awaiting-parts problems.

Further, there should be: a major reduction in backorders; a reduced logistics footprint; improved reliability; reduced diminishing manufacturing sources and reduced material shortages and obsolescence issues; and decreased operating and support costs.

Relentlessly adding value to customers through enhanced experiences and outcomes is critical for any company, regardless of contract type, supported by a culture of continuous improvement. The key is to understand how to focus differently to match the demands and incentives of different contract types.

Two key elements, regardless of contract type but especially valuable on performance-based logistics are: strategic analysis and planning, a predictive capability to improve forecasting and long-term planning across the portfolio, and operational excellence, performance-focused behaviors at all levels of the enterprise.

As for strategic analysis and planning, decisions to pursue a PBL contract with specified levels of availability and reliability must be based on rigorous data-driven analysis and not gut-feel assumptions, or worse yet — a “we’ll figure out how to make it work” mentality.

Unfortunately, many companies performing transactional often cost-reimbursed work in defense have exactly this approach. Assessing whether an organization is able to deliver the contract, and do so profitably, includes analyzing alternate scenarios to evaluate the robustness of potential benefits under a wide range of potential conditions, to quantify and highlight key customer obligations and the impacts of them not meeting these or the impacts of customer changes, and assessing and prioritizing the best options to improve performance.

It is important to be able to assess the full impacts over time. What are the key performance drivers, baseline conditions, gaps and risks and potential mitigation? Ongoing analysis as a program evolves is important, including rapid assessment of the full impact of changes. Over time, analysis is enhanced through developing a database of past programs and an ability to analyze differences on upcoming potential programs. This information is critical to monitor program performance, enhance decision-making, and support rapid and effective negotiations with customers on changes.

The essence of operational excellence is delivering value faster, more reliably and at lower cost. If an organization does not have this culture already embedded, then it’s likely that all its programs — not just PBL — are seeing erosion of margin and customer relationships. If there are pockets of an organization that embrace a culture of continuous improvement, it is critical to change incentives so that it drives this across the entire organization as most programs will draw on shared functions such as engineering, supply chain, sourcing, procurement and manufacturing.

Results-driven, high-performing organizations have clarity and alignment on mission and vision; defined business and program objectives, metrics and accountability; efficient and digitally streamlined availability of accurate data; and a commitment to process improvement and a deeply-rooted culture of continuous improvement. This is an organization that will make PBL contracted programs benefit both the customer as well as its bottom line.

So, does performance-based logistics work? For the customer, it absolutely improves desired outcomes while simultaneously lowering total lifecycle costs. For the supplier, results are mixed. While doing whatever it takes to deliver contracted deliverables, at times through brute force, program margins are put at risk.

Bringing both customer and supplier perspectives together, one of the biggest customer challenges with performance-based logistics is when their needs change and they struggle to adapt contracts to reflect these changing requirements. A supplier that is strong on strategic analysis and operational excellence is best placed to be able to rapidly understand the impacts of change, be able to clearly explain and quantify the impacts for customers, and identify the best way to mitigate the changes.

This gives both sides what they need — for customers the ability to adapt as their requirements evolve, and for suppliers to do so from a position of strength that builds customer confidence, enables them to deliver, and yet ensures strong profitability. Both sides get what they want and deliver the improved value for money that the Defense Department has struggled to achieve in its relationship with industry.

James Marceau authored and colleagues Tom Mullen and Mark Sandate contributed to this article.